Countries are deregulating their banks — what about Canada?

Donald Trump started a race to the bottom, but in some races Canada likes to place last

“Deregulation” can be a dangerous word. In banking, it is tantamount to desecration. Even laypeople know (or think they do) that unregulated banking systems are prone to crisis. Without regulation, there is nothing to stop greedy bankers from making too many bad loans, which show up as assets on their balance sheets before a critical mass of borrowers default, taking the whole financial system down with them.

At least that was true for a time. Deregulation is not the dangerous word it once was because necessity has shaken the world out of cognitive autopilot: some of the biggest Western countries in the world are pursuing a deregulatory agenda in their financial sectors.

Trump’s deregulatory agenda has been most aggressive, earning the label “reckless” from the editorial board of the Financial Times. A plan to require banks to hold more capital in reserve—the so-called Basel III “endgame,” an international accord that came out of the 2007-09 financial crisis—is expected to be diluted or shelved. Financial consumer protection took a hit, after the acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau ordered his staff to stop working. The U.S. is also flirting with crypto. Since Trump was inaugurated, SEC-initiated lawsuits against crypto companies have been dropped and policies have been repealed to make it easier for banks to hold crypto assets on their balance sheets.

This month, British prime minister Keir Starmer had a similar vibe when he took aim at the “cottage industry of blockers and checkers.” So far, he has abolished the country’s payment system regulator, which had long been in a bitter battle with UK banks over how to protect consumers from fraud. The Financial Conduct Authority also scrapped its plans to name and shame companies under investigation for harming consumers. And after delaying its own implementation of the Basel III endgame, the UK’s prudential banking regulator decided not to impose stricter diversity and inclusion rules on financial institutions.

Even Germany, Italy, and France are pursuing a deregulatory agenda. Last year, they jointly called on the EU Commission to reconsider its plans to toughen bank oversight and “put stronger emphasis on the competitiveness of the financial sector, particularly banking, and its capacity to…finance key European goals.”

Race to the bottom to get to the moon

International cooperation on banking regulation is essentially a bargain between countries to collectively suppress profitable risk-taking in exchange for systemic stability. The Trump administration reneged on its side the bargain after signalling its rejection of the Basel III endgame, causing the whole of it to unravel.

When one country defects, it’s rational for others to follow. If one country relaxes its banking regulation while others do not, banks in the first country are going to have more capital and economic opportunity to turn a profit than banks in the others. This is a problem because while countries need stable banks, they also need competitive ones. Their banks need depositors and investors, who are attracted to returns. Countries also need their banks flush with liquidity to finance national projects, as taxpayers have their limits. Indulging in this self-interest is irresistible amid the decline of the United States as a trustworthy economic and military ally.

So what is Canada, with its exceptionally stable banking system, to do?

The bare minimum, apparently. Last month, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions indefinitely delayed its plan to implement the final Basel III requirements. But Canadian policymakers haven’t done much else to make being a financial institution easier. In fact, they have been making it harder. Before Trump was inaugurated, the Canadian government was enacting bank-specific taxes, reducing the revenue banks can earn from issuing credit cards, and empowering Canada’s financial consumer protection regulator to investigate and fine banks. The feds are continuing to make it harder now, as if they missed the international memo. This month, they capped the NSF fees banks can charge customers.

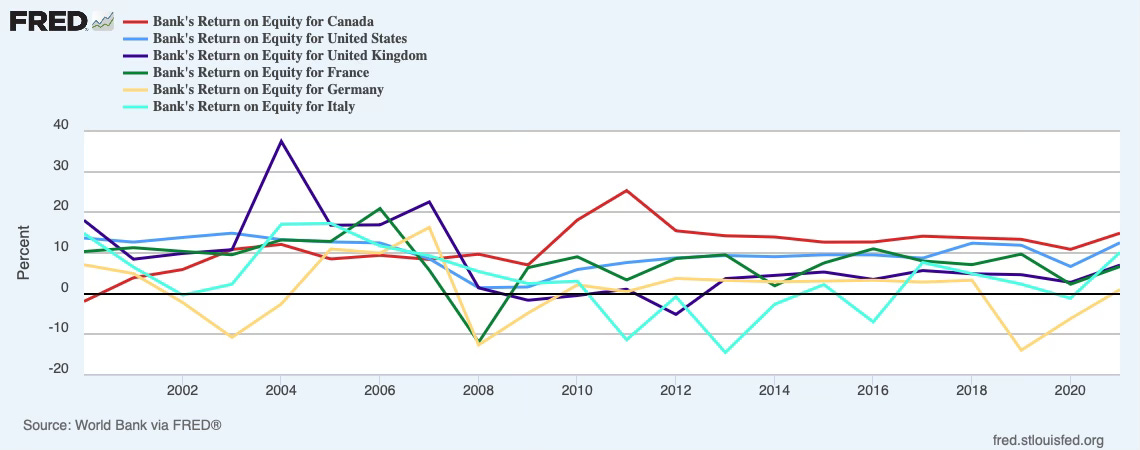

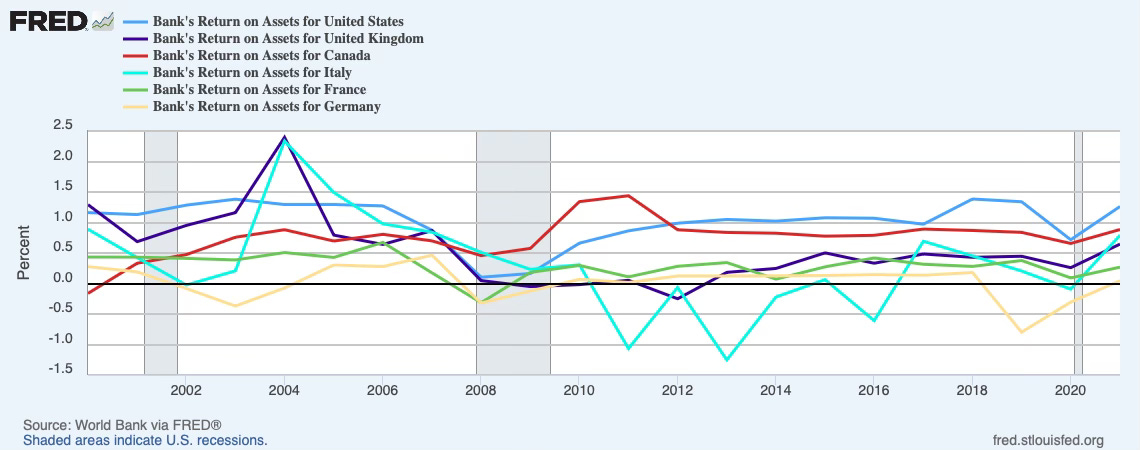

Perhaps Canadian banks don’t need the extra help. The biggest of the bunch—TD Bank, BMO, RBC, CIBC, and Scotiabank—are among the 100 biggest banks in the world by asset size. Collectively, they have a presence in more than 50 countries. Canadian banks are highly profitable, outperforming many of their peers in generating a return for their shareholders and on the assets under their control. Maybe policymakers can afford to make life harder for financial institutions because life in Canada is so easy.

The country’s top banking lobbyist begs to differ. As the Canadian Bankers Association told the government last year, banks here are too heavily regulated. The CBA called for a slew of deregulatory measures, including “steps to review and rationalize the regulatory burden imposed on the banking sector.” It pushed for the elimination of bank-specific taxes, such as the Financial Institutions Tax and the Canada Recovery Dividend. The banking lobby also asked the government to reduce how often banks need to get regulatory pre-approval to conduct certain business.

It’s plausible a bit more banking deregulation would be good for Canada. While it would let the big five banks take more risk to generate more profit, the big five likely wouldn’t because they’re notoriously risk averse, holding more capital in reserve than their regulator requires of them. What deregulation would do is unleash Canada’s smaller banks to increase the competitive intensity in Canada’s banking system altogether. Some of Canada’s smaller banks report feeling more constrained by OSFI than they believe is warranted by the (smaller) risks they pose to the financial sector. More competition within the industry can up everyone’s game, including the big five’s, making Canada’s financial sector more productive as a whole.

Two races are going on at once

Though deregulation may no longer be the dangerous word it once was, it’s hard to imagine such an agenda getting the political attention it needs to come to life in Canada. Our politicians take years to find the courage to introduce more regulation in the financial sector when the regulation is misunderstood, such as open banking. When Conservative MP Ryan Willams said the Conservatives will go “huge” on open banking if they form government, the comments on social media were telling. “Ugh,” said Reddit user and top commenter akinto29. “There’s a reason why Canadian banking regulations are very strict: banks fail otherwise.”

In this election campaign, expect no one to promise to deregulate Canadian banking. More than anything else, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre needs to distance himself from the deregulatory Donald Trump, and offer himself up as an alternative to the prudent Liberal leader Mark Carney. Carney would have more license to challenge the conventional wisdom on banking, earned from his past as head of the central banks in Canada and the United Kingdom. Still, while deregulation may generate bigger profits for Canada’s banks, it’s not going to generate the necessary votes for Carney.

Post-election is a different story. Either of two leaders would be wise to give the Department of Finance the green light to explore how Canada can deregulate its banking system in light of this new world order, where we have no choice but to rely a little more on ourselves. A populist reformer may be more comfortable with deregulation than a prudent technocrat, but what is true of both Poilievre and Carney is this: they’ll need to form a majority government to entertain deregulation of banking in earnest. Only a stable hand can confidently loosen its grip.

" As the Canadian Bankers Association told the government last year, banks here are too heavily regulated." They didn't mind the regs that kept foreign banks down and protected their oligopoly though.