Econometric governance

The strange truth about Canadian banking

Prime minister Mark Carney recently quipped that he will “govern in econometrics.” The jest was a riff on ex-New York governor Mario Cuomo’s dictum that you campaign in poetry and govern in prose. Of course, good governance is more art than science. Balancing opposing values is messy, irreducible to Greek symbols on a page. No quantity of data will prove the perfect balance beyond a reasonable doubt. Yet leaders must decide. Good governance is prevailing over moral and instrumental uncertainty. It’s here where a fluency in science—and, yes, even econometrics—can be useful.

A bit of econometrics would have been useful the other week, when National Bank CEO Laurent Ferreira praised Canada’s banking “oligopoly” as “a good thing for the country.” Fintech leaders and public intellectuals threw out missives like haymakers. They asked how the oligopoly can be a good thing while bank fees are high, small-business credit is scarce, and the big banks are uber-profitable, earning some of the highest returns on equity around the world.

Mark Twain wasn’t talking about banking when he said the truth is stranger than fiction, but he could have been. If a novel were being written about Canada, big bank CEOs would gather in smoky rooms, away from prying eyes. They would weaponize the law to keep their competitors out, while their loans would have the same interest rates, and their accounts the same fees. There would be no escaping it. The blue bank would be just like the red one, which would be just like the green one, which would be just like the other few.

The truth is Canada’s banking system is real and, therefore, strange.

Econometrics suggests the so-called banking oligopoly is more competitive than it looks. Six banks control almost 90 percent of the market, but economists who win Nobel prizes for their work in market power and regulation say that doesn’t mean much. What matters is how contestable a market is, which is just another way of saying how easy it is for new firms to enter and claw away at incumbent profits.

It turns out a market needs no more than a few firms to be competitive. Studying bank entry in thousands of small U.S. counties, economist Nicola Cetorelli found that the biggest shock to incumbent profits came when the third and fourth banks entered the market. Adding a fifth and sixth squeezed margins even more, but just barely. In concentrated markets, where collusion is likeliest, banks didn’t need a dozen competitors to honestly compete.

There are other clever ways to test the contestability of markets.

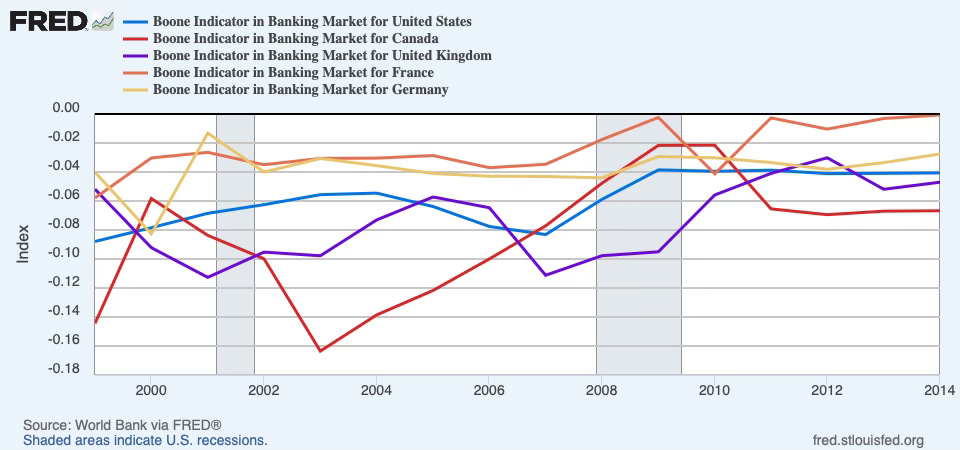

Economist Jan Boone figured that if a market is competitive, then more efficient companies should be more profitable. So he developed a measure called the Boone indicator that estimates how strong this efficiency-profitability relationship is. The Boone indicator is like a golf score. Lower is better. If it’s less than zero, then more efficient firms are turning bigger profits, which means the market is showing signs of competition. Zero or higher and the inverse is true.

According to Boone’s method, Canada’s banking oligopoly was more competitive than the banking systems in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany (at least until 2014, the last year for which data are publicly available). Boone’s isn’t the only way. There are other measures, also with arcane names, and which also hinge on esoteric economic theory. Many of them reinforce what the Boone indicator shows—that Canada’s banking oligopoly is more competitive than its name implies.

Still, econometrics has its limits.

Nuance is lost in aggregate measures of competition. Consider that banking isn’t one thing. It’s deposits, consumer and business lending, payments, wealth and cash management, investing, and more. Averaging the level of competition across all of them can be misleading, like taking the temperature of someone with their head in a hot oven and their feet in a liquid-nitrogen freezer. Their average may look normal, but they’re far from healthy. They’re maimed or dead. Taking the competitive temperature of banks is the same: an anti-competitive payments market can be obscured by a competitive lending market.

What’s more, econometrics isn’t legitimizing. Prime ministers govern people who have feelings, not falsifiable hypotheses. It doesn’t matter if an econometric model says credit card interest rates reflect fair risk pricing, or big banks who pay lower interest rates on deposits are actually out-competing small banks who pay higher. If people feel gouged, ignored, or powerless, then the feeling is all that matters.

Prime ministers would be wise to govern in econometrics only when people don’t have strong feelings.

This is fortunate for would-be reformers of Canada’s banking system, about which Canadians seem to have weak feelings. According to a recent poll, making financial services work better is the least important of the 12 things the federal government should prioritize. The irony is that the econometrics may agree.

And that, too, is something worth modelling.

Great piece. We are well banked in many regards and the data would reinforce that.

On the other hand, it stands to reason that there are big nascent opportunities in the sector, that will largely be driven by competition and globalization.

The UK government has done a good job building their fintech industry on offence. Last number I saw was 13,000 jobs created in London.

Many US companies have engineering offices in Toronto. Those companies largely build products to serve only US customers.

This is akin to mining oil but not refining it.