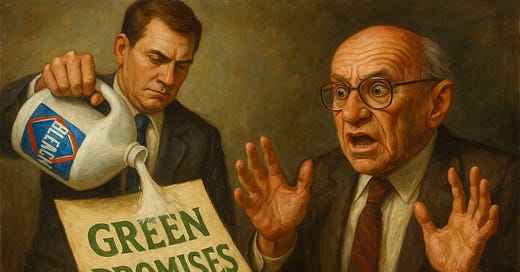

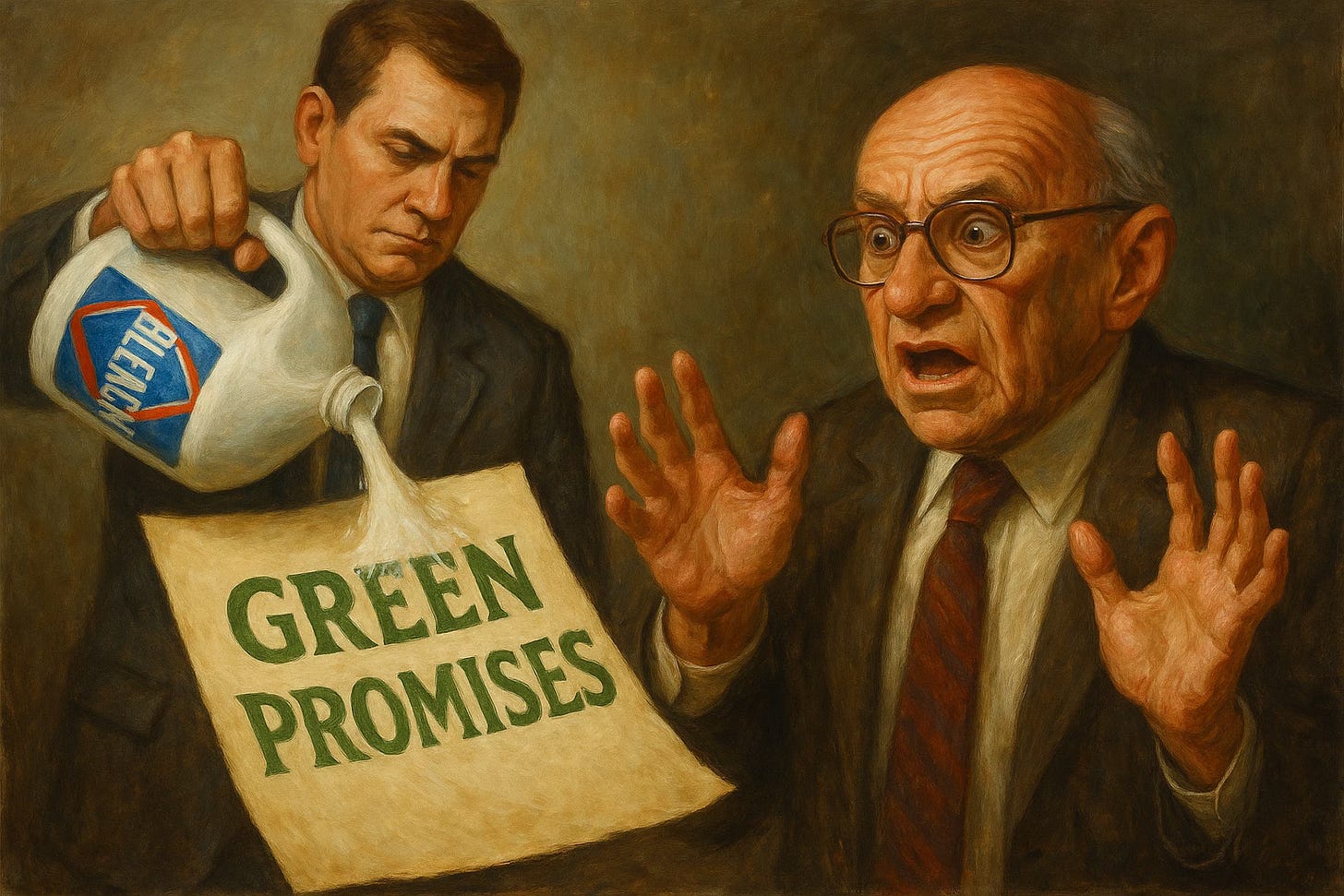

Greenwashing rules are bleaching the truth

In aiming to crack down on misleading claims, Ottawa has made honest ones harder to make.

The libertarian Milton Friedman once quipped that if you put the government in charge of the Sahara desert, the result would be a shortage of sand. Though a reflexive aversion to government is bad for the brain, there is wisdom in Friedman’s joke because it’s prophetic: Ottawa recently passed anti-greenwashing rules to get more transparency and now, ironically, it is getting less.

Last year, the federal government made it easier to crack down on companies that make false or misleading environmental claims. In other words, Ottawa wanted more transparency, and so it raised the cost of transparency. The result was predictable: less of both. Canada Pension Plan dropped its net-zero emissions target, while RBC abandoned its sustainable finance goals. The Pathways Alliance, a group of oil sands companies with its own “green” pledges, scrubbed its website of content.

Some supporters of the anti-greenwashing rules called this an overreaction, and others a tacit admission that none of these companies was ever planning on living up to its green promises. But I don’t think we can be sure of either proposition.

The argument put forward by the latter group, which is accusing the aforementioned companies of being Frankfurtian bullshitters or worse, is impossible to verify. A company’s disregard for the truth is unobservable when it is making a possibly credible commitment. Of course, we’re allowed to have hunches. We’re allowed to form beliefs. But to form a justified belief and make a public accusation we should need to meet a higher evidentiary standard. This argument, as it stands now, is conjecture.

The former group, which argues that the aforementioned companies are overreacting, is more plausible. These supporters of the anti-greenwashing rules argue there is nothing draconian about holding companies accountable for their claims. A drug manufacturer can’t just claim its drug will lower levels of bad cholesterol. Nor can a cattle farm make the same claim about its sausages by saying its sausages are all protein and no saturated fat. Drug manufacturers have to do large, randomized, controlled trials to prove a drug’s safety and efficacy, while a sausage maker has to comply with food labelling requirements.

This argument loses its steely finish once we accept the innocuous premise that companies should be held accountable for lying. They decidedly should. But how the feds hold companies accountable can turn this otherwise noble mission into a wise or foolish one.

When Ottawa passed the anti-greenwashing amendments to the Competition Act, it made it easier for the Competition Bureau and private parties to legally challenge a company’s forward-looking, environmental claims. Unlike cholesterol levels, or the fat and protein content of a sausage, a 2030 emissions pathway is built on contestable scenarios and assumptions, making just about anything easier and harder to prove at once. It also set a vague standard by which companies would need to substantiate their environmental claims if challenged: “adequate and proper substantiation in accordance with internationally recognized methodology,” which is new and undefined in Canadian law.

The idea that companies are overreacting is probably wrong.

With new powers under his belt, Matthew Boswell, head of the Competition Bureau, told a crowd late last year to expect a “more aggressive and active enforcer.” This is the same Boswell whom Bay Street thinks is a “radical” and “cowboy” commissioner. Rhetoric doesn’t always match reality, but rhetoric isn’t lost on people. And it’s people who advise bankers on the legal risks they should and should not take. I’ve spent enough time around RBC’s lawyers to know that the institution is afraid of its shadow. It ought to be, since it is a formidable bank and banks are hard-wired to be neurotic. If there is little upside to doing something—such as voluntarily committing to internalizing your own externality—and a lot of downside—legal and reputational risk—then the answer is obvious: don’t do it.

Defenders say the standard to prove environmental claims won’t be a high bar, and so there’s no need to retreat from making any claims whatsoever. But how do they know? Talk is cheap, and so it’s easy to say. It’s hard to do, however, since getting it wrong can expose a company to a fine of up to 3 percent of global revenues—and the Competition Bureau’s guidance doesn’t really tell a company how to get it right.

Which brings me back to where we started: Friedman’s joke.

In the long-run, the quip is less funny not because we’re all dead, but because it’s less true. Ottawa’s anti-greenwashing rules are reducing transparency in the short-run because firms are appropriately reacting to legal uncertainty. Still, there is no reason to think there will be less transparency forever. Transparency will increase in the long-run if case law and supervisory guidance evolve to give companies a better sense of which standards they can use to substantiate their environmental claims.

If the government wants to crack down on dishonest or flimsy environmental commitments, that’s fine. But it also has to show the market how to be honest.

Do you have any idea whether the legislators ever reached out to some target companies to help them design realistic, practical provisions for this law?