When you want to let someone down without drawing attention to their role in your decision, it’s normal to tell a white lie. “It’s not you,” you say. “It’s me.” When breaking up with a partner or ending a friendship, this little line works wonders if you’re more Benthamite than Kantian. Relationships are complex. In many cases, there is no right or wrong. There is only function and dysfunction. Why damage someone’s self-esteem for something that isn’t their fault in any moral sense?

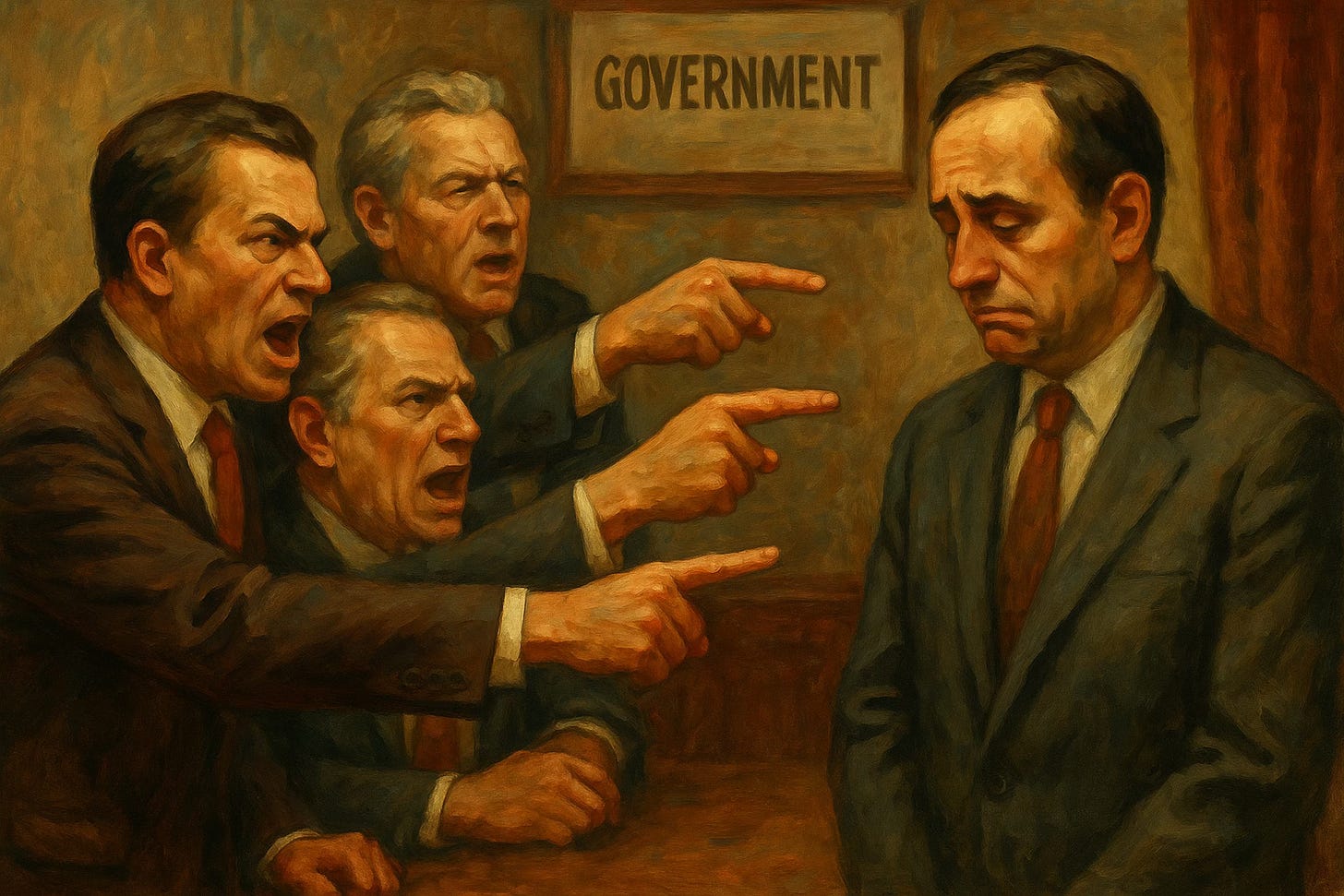

Canada’s business leaders don’t observe this courtesy. They lament Canada’s sluggish economy, but they blame the government instead of themselves. Though business leaders are responsible for the decisions that, in the aggregate, make up the economy, they will tell you the reasons for their collective failure is that they aren’t getting enough tax cuts and subsidies, the government isn’t procuring their products or services, and policies and programs aren’t advantaging them over the international competition. It’s you, in other words, not me.

Maybe that’s because they have a chorus of academics behind them, arguing the reason for Canada’s poor economic performance is the lack of a good industrial policy. It’s a message relayed so confidently that you would be forgiven for thinking it’s obviously true. You would also be forgiven because industrial policy is common around the world. Countries use it to grow their economies, develop “green” technology, protect national security, and gain geopolitical power they can check their rivals with.

The truth is that even the intellectually serious proponents of industrial policy don’t know how effective it is.

Of course, industrial policy can be effective. Cartoonish variants of neoliberalism are imperfect. In libertarian utopia, the economy doesn’t generate enough new knowledge to innovate with. Scientific discoveries and manufacturing know-how are expensive to come by, but they’re also cheap to copy, and so pioneering firms underinvest in them. An unfettered economy also doesn’t think enough about national security. The invisible hand is partial to components for military drones from abroad, where they are cheap and readily available—except in times of war, when access can be cut off. These are textbook market failures, and industrial policy is the theoretical corrective.

The problem with industrial policy is that we don’t live in a textbook. Market failures are unobservable. At best, our tools for sizing them up are imperfect. So are the politicians and policymakers who swoop in once it’s clearer that markets have failed. Under the constant pressure of special interests, the government is prone to being commandeered by pork barrellers and corporate grifters.

The experience of East Asia is often cited by proponents of industrial policy, and the experience of Latin America by the skeptics, but the more important question is this: which experiences are the exceptions, and which are the rule?

To the best of our knowledge, the efficacy of industrial policy is highly context-dependent, and even then the gains from it are modest. It’s hard to find big, permanent effects that are statistically significant. A staff note published this year by the International Monetary Fund found that domestic subsidies in over 100 countries over the past decade boosted productivity, investment, and patent applications in the short-run, but the gains faded after few years. Export incentives durably boosted productivity, but only modestly. The study concluded that there are more cost-effective ways to boost economic performance, such as reducing the overall regulatory burden on businesses, promoting more competition, and liberalizing trade.

Proponents of a more involved industrial policy remain optimistic because they (correctly) believe the aforementioned studies are flawed. By including so many policy instruments, countries, and years in the scope of analysis, such studies conflate good industrial policy with bad. It’s like studying the entire population to understand the effect of geniuses on society.

This has led other researchers to zoom in a little more. Nathan Lane found long-lasting benefits from South Korean industrial policy in the 1970s. Réka Juhász found a boon to France’s cotton spinners when she studied the effects of the Napoleonic blockade, which prevented the import of British cotton in the early 1800s. Though it’s tempting to look at these success stories and conclude that they can be replicated here, doing so would be premature. As interesting as these newer studies are, they aren’t generalizable. More evidence is needed to believe that what worked in Napoleonic France or 1970s South Korea will work anywhere else.

Zooming in shows us what good and bad industrial policy is, but it doesn’t show us whether good industrial policy is more likely than bad in the first place. Industrial policy doesn’t fall from the sky. It originates in the broken system it’s meant to fix. It’s the result of a long and opaque negotiation between the government and special-interest groups. Having been in the middle of a few of these negotiations myself, I can assure you that benevolent philosopher kings and queens are few and far between.

If industrial policy isn’t already turning Canada’s economy around, then why should anyone believe it ever will? That question is only a little rhetorical. The government has been experimenting with industrial policy over the years. It subsidizes private-sector research and development. The feds tried to create “superclusters” to supercharge economic growth. There are public financing programs to help Canadian businesses scale and access global markets. And let’s not forget all the sector-specific incentives, such those for the auto and mining industries.

The more one looks at results, the less impressive all of the industrial policymaking looks. Tax credits and subsidies for R&D struggle to pass a cost-benefit analysis (which may say a lot about Canada considering all the evidence in favour of subsidizing R&D). Politics made “superclusters” a bit more like supersuckers of public money with middling returns. Public financing programs are not solving capital-access problems for the smallest and highest-risk business. And the sector-specific incentives top up Canada’s ever-increasing corporate welfare state—all of this, apparently, for sluggish economic and productivity growth.

Still, there is a common refrain: if only we threw more money at these programs, or if only we hired more talented people in government to better design and implement them, then we’d see better results. It’s not us, Ottawa. It’s you.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with playing the blame game. Blame is what you assign to someone when they fall short of a normative standard. It’s a useful thing to assign when the standard is socially beneficial, like the one against wanton violence. Sometimes, however, normative standards are solipsistic. This is when they cease being beneficial for anyone but the person furrowing their brow and pointing the finger.

Recall the adage that there are two sides to every story. In this one, maybe Canada’s business leaders ask the government for money because they want a fat payout at the expense of taxpayers. And maybe the government is captured by special interests in cahoots with opportunistic politicians, who pick the industrial policy that boosts their chances at re-election. Business depends on the government for its success, and the government on business for its own.

Perhaps lies are being told. But they aren’t white lies like a break-up excuse. They’re profitable ones. They’re just paid for by the rest of us, while the economy stays exactly where it is: under-performing and over-subsidized.