Why Ottawa still hasn't regulated stablecoins, and why that may soon change

And why, if it does, Canada’s crypto scene won’t get what it wants

The future was here yet never arrived. Bitcoin was the future of money when its mysterious inventor, the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, released it into the wild in 2009. It was predicted we’d be able to visit our favourite online stores and pay for everything in our carts with it. Fast forward to today and we’re still waiting. Few merchants accept it as payment because it swings wildly in value. Depending on the day, your fraction of a bitcoin could buy you a nice sweater, a bag of chips, or an all-inclusive trip to the Caribbean.

This is why the feds haven’t embraced the latest promise to cross their desk: that fiat-backed stablecoins are the future of money, as bitcoin was supposed to be. Canada’s crypto scene has been asking Ottawa to update its laws to recognize stablecoins as alternative monies and means of payment. But the federal government has been ignoring the requests.

It doesn’t help that fiat-backed stablecoins are like bitcoin’s quiet, unassuming cousin. Bitcoin is a polyamorous, libertarian swinger with dyed hair and obscured body piercings. A stablecoin is someone who used to be a little rebellious, but is now a straight-edge accountant, in bed and sound asleep by 9pm every night. Bitcoin commands attention because it’s exciting, which is also why it doesn’t work as money. A fiat-backed stablecoin works precisely because it’s boring, although being boring makes its revolutionary promise easy to miss.

A fiat-backed stablecoin is a digital asset, and it’s supposed to be fully and transparently backed by fiat currency and other high-quality assets. When it is, its price is effectively pre-programmed because you’re able to redeem one stablecoin for one dollar at any time, anywhere, and on demand, no questions asked. This is what keeps its value stable, which is what makes fiat-backed stablecoins a more viable alternative to government-issued money than bitcoin.

Fiat-backed stablecoins were originally a tool for crypto-traders to deal with the volatility of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. To protect their portfolio against crypto’s wild swings, they’d trade their bitcoins for stablecoins, which kept a stable value. This was superior to trading for cash, which came with delays due to banks’ antiquated transfer systems, and which may have triggered tax obligations if they realized any gains. Using stablecoins to execute these transactions was fast, frictionless, and cheap.

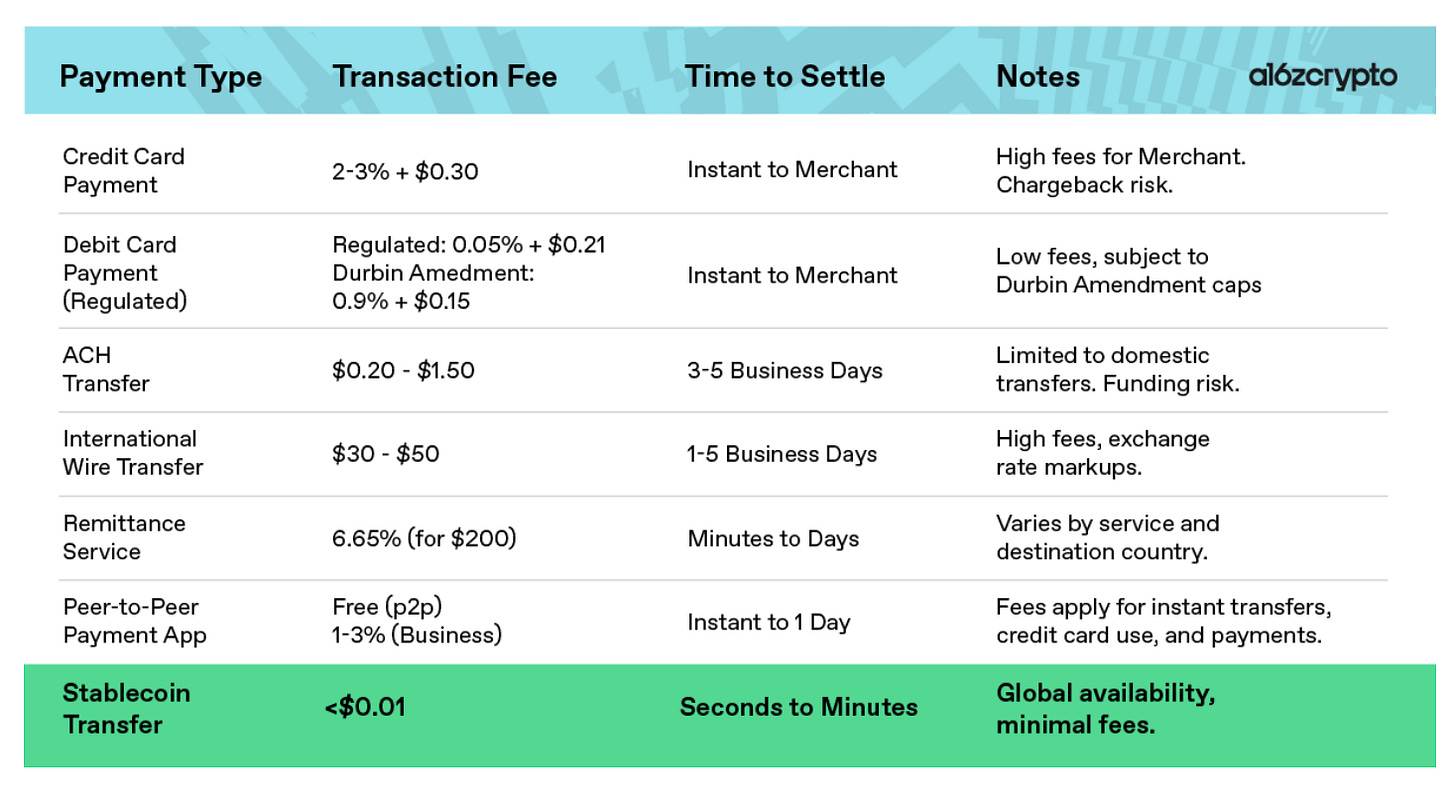

It wasn’t long before people thought they could make all payments fast, frictionless, and cheap—the opposite of what payments are today, according to this table from venture capitalists Andreessen Horowitz, who believe fiat-backed stablecoins will “eat payments.”

Payments are already being munched. Last year, Stripe started letting merchants receive payments in USDC, a stablecoin issued by Circle. Within 24 hours of launching, they saw merchants taking stablecoin payments in more than 70 countries. PayPal offers its own stablecoin, transferable between PayPal accounts and out of them, and redeemable for one American dollar. Visa has also been enabling its bank clients to give consumers and businesses the option to transact with stablecoins.

Stablecoin usage is on the rise, but your payment options at the local Loblaws are still cash, debit, or credit. Try asking your cashier if they take stablecoins and watch how their face turns.

In Canada, fiat-backed stablecoins are still just a promise about the future of payments. Here, the prevailing wisdom is they mostly help investors hedge against crypto volatility. Elsewhere, that’s not true. In developing countries with debased currencies, they’re alternative monies. They also help families and humanitarian organizations move money across borders when banking infrastructure is scarce, or when banks refuse to get involved because there’s a risk of getting caught up in a money laundering or terrorist financing scandal (sanctioned governments and criminals also use stablecoins to move money across borders). In Canada, as alternative monies or means of payment, fiat-backed stablecoins remain an experiment.

Small “c” conservative governments don’t regulate experiments. They regulate results. That’s why rather than treating fiat-backed stablecoins as alternative monies or means of payment, as Canada’s crypto scene had asked, policymakers decided to give them the same treatment as cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and regulate them as securities. Last year, Circle became the first stablecoin issuer to register with securities regulators.

Canadian policymakers may soon be forced to change their minds.

South of the border, policymakers aren’t passive observers; they’re rigging the experiment to get their desired results. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has clarified that fiat-backed stablecoins are not securities when they deliver as promised: pegged one to one to the American dollar, fully and transparently backed by high-quality liquid assets, and redeemable on demand. U.S. lawmakers have also introduced bills in both the Congress and Senate to comprehensively regulate stablecoins as means of payment. The statecraft seems to be working, with Bank of America saying it plans to launch its own stablecoin once U.S. legislation is passed.

The European Union has also skipped past experimentation. Under the bloc’s crypto-asset regulation, which came into force in 2023, stablecoins even have their own category: “e-money tokens.” The framework applies across member states, offering the kind of legal clarity that’s still missing in North America. It’s not an easy framework to comply with—the requirements are strict—but it is a clear one. It’s already attracting issuers who would rather comply with a fit-for-purpose framework than have to prove one is needed.

Canadian policymakers are also being pressured from within to do more about stablecoins. Peter Routledge is the head of Canada’s banking supervisor, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. As a regulatory imperialist, eager to expand the power of OSFI, Routledge’s views are no secret. “There are some stablecoin arrangements that, when I look at their balance sheets, look an awful lot to me like banks,” he told a parliamentary committee last year. “Those institutions, if they have balance sheets that look like those of banks, should be regulated like banks.”

How to regulate stablecoins is not a straightforward question, since it can be a metaphysical question as much as a technical one. If a stablecoin is not a security, for example, then what should it be under the law?

Some would agree with our banking regulator-in-chief that stablecoins should be treated more like private monies, issued by institutions doing what banks do, which is accepting deposits and then generating a return on them, intermediating between savers and borrowers. If stablecoin issuers take cash from their customers, and then use some of that cash to buy treasury bills and bonds to turn a profit, it’s hard to argue they shouldn’t be regulated by OSFI like banks, either under the Bank Act or a more tailored version thereof for stablecoins. Runs on stablecoins, if they were widely used, could destabilize the financial system.

Still, stablecoin issuers aren’t obviously in the business of banking. Circle isn’t a lender, for example, taking consumer funds and using them to offer mortgages to consumers and commercial credit to businesses. Circle holds cash and cash-like assets such as treasury bills in reserve, just like PayPal and Wise, who are regulated as payment companies, rather than banks. In Canada, payment companies are regulated under the Retail Payment Activities Act, which compels them to segregate customer funds from their own and meet operational standards.

Financial regulation is built on a taxonomy of hazy distinctions.

Others don’t think stablecoins are worth the trouble. In 2021, a man of international acclaim and respect delivered a prestigious lecture to the central banking community. He argued private issuers of money are inferior to central banks, which could issue their own digital currencies without imperilling the financial system, and without the hassle of building trust from scratch. To him, the issuance of money is too important to be left to the market because even one failure is “one too many.” The man’s name is Mark Carney.

If you asked Canada’s crypto scene what the feds should do, you’d get an impossible answer.

For stablecoins they want prudential oversight, which is what OSFI provides, but they don’t want OSFI to provide it. Instead they want the Bank of Canada to regulate fiat-backed stablecoins under the Retail Payment Activities Act. But the Retail Payment Activities Act isn’t really prudential regulation, as it doesn’t regulate non-bank payment companies to minimize their risk of failure. Only prominent and systemically important payment companies, subject to Bank of Canada supervision under the Payments Clearing and Settlement Act, are regulated to avoid failure. But no one in Canada’s crypto scene has (publicly) asked for the Payments Clearing and Settlement Act to apply to stablecoins.

It’s up to policymakers to reconcile tensions and fill gaps in any policy proposals being considered. Bitcoin made a promise it couldn’t keep. Stablecoins may keep their promise, but only if Ottawa serves as their guarantor. The feds can try to shape the future of payments—or keep waiting, before the rest of the world drags them into it anyway.